August 14, 2011

All Of These Things That Have Made Us

All Of These Things That Have Made Us

By Tom Spurgeon

By Tom Spurgeon

"You have a life-threatening condition," the doctor said.

"We need to get you somewhere where they can operate on you," he continued, the words tumbling out of him.

"We need to get you there immediately." A breath.

"We have a hospital. We have a surgeon. When we have an ambulance, you'll go."

He stepped away from the room, closing the curtains behind him with a shriek of ball bearings on a metal track. I liked this doctor. He had a broad smile. He rapped his knuckles lightly on the edge of the counter when he turned away to contemplate a piece of advice, talking his way through various bits of specific medical knowledge. I found this endearing.

What he said this time, right to my face, didn't settle in for about 30 seconds. I remember laughing at least once, a memory-laugh that bubbles up when you remember something amusing, about what exactly I have no recollection and probably didn't know right then, either. I turned and looked at my Mom, the parent and person whom I'm most like, in the room with me by accident. "Can you take out a pen and piece of paper? I guess I need to tell you some things."

None of them were about comics.

*****

That's a lie, of course. Plenty of them were about comics. Four of the seven people outside of my family I wanted her to contact were I to die in the next several hours were people I'd met through comics. A pair of them were former co-workers. One was an ex-intern. One was simply a guy with whom I became friends because we both enjoyed making Moses Magnum jokes on-line. My friends.

You could do far worse than to build a lifetime of friendships with the people you meet in comics. Far, far worse. I'm not sure you could do much better. As much as I'm made uncomfortable by a vision of comics that lacks the comics themselves, a way of approaching the professional and artistic communities that could without blinking substitute designer baskets or arcade games or action figures for the comics medium, I understand the appeal of wanting to stay around smart, curious, kind and mostly forgiving people for as long as possible, even if one's passion for the art form fades.

I've always been grateful that I came of age at a time when engaging the entirety of pop culture was an act of scrambling to find out about things and then to track them down. I'm equally thankful that I made my first adult friends without the comforting approximates provided by social media. I benefit every day from the act of casting off most of what had come before and building something that was on personal terms entirely new and, in many ways that count, lasting. That I had to travel 2762 miles to find people that understood all of my jokes, that believed in many of the same things I did in a thousand different, fractured ways, that were willing to make a fresh appraisal of who I was and what I had to offer and where I was lacking, somehow that journey made those brief years that much sweeter, or at least makes them so in memory. A couple of months into my time in Seattle, I used to find reasons to work at night just so I could listen to a certain group of people talk to one another. Except for the fact that so many of us were deeply unhappy, I'd gladly live through great, sweeping portions of that period in my life again.

Mom and I also talked about my comics collection. This is an absurd thing to crowd into anyone's last few hours with any loved one, but I hadn't potentially left any other three- ton piles of cultural ephemera sitting around with which folks would have to deal were I to absent myself. Just in case you were wondering: there are no good answers for instructing others what to do with all those books, at least none that flash to mind while a crowd of people 12 feet away foist their measured, furious attention on a nine-year-old with a scorpion sting. Maybe those people that disengage with the form have a point.

*****

It was my first IV, my first ambulance ride, my first encounter with Morphine, my first hospital bed, my first flood of antibiotics, my first time meeting a group of surgeons, my first discussion of a Shooter-era Marvel market share sized mortality rate, the first time I'd been put under.

*****

Sometimes I worry I stick around the comics industry because it's the easiest thing I can do. It's almost impossible to get drummed out of comics. You can half-ass it for forty years. You'll always be welcome; if you're lucky, you might win an award or even get into a Hall Of Fame. We're an industry of more later, new creative teams, to be continued, we'll stop putting them out late when you stop buying them, it's great to have you back, all that is water under the bridge, you should do a few more issues, of course I know who you are.

That doesn't mean there

aren't people in comics that work extremely hard. Many do. Maybe most do. In fact, the indolence exhibited by some wouldn't be possible without the rigorous energy of others that don't have the space to be unproductive for even a half day, that don't have the time to google themselves, that couldn't fathom participating in an on-line debate. I've talked to the children of strip artists whose primary memory of their fathers and mothers is that person at a drawing board, desperate to get away for a few moments but deciding with an almost whole-body resignation to continue working while life-moment X, Y and Z unfolds nearby. It's just that in comics so many

pretend to work hard, too, with a thousand strategies to let themselves off the hook for this minimal effort. More comics people than any others I know have more days where they go to work, stare at things, have a conversation or two, do something on their computer that could be argued in the kindest court in the land to have something to do with their jobs and then retreat home.

It's always denied. According to personal testimony, no one with a comics job ever puts in an easy day. At some point, some comics people began to boast of their work output, portraying themselves as art heroes putting the time in and loving it, or at-wit's-end time managers struggling to carry a heavy load -- people that watch themselves work rather than just work. You'd see them send out frequent high-fives to fellow hard-workers, saying what they're doing out loud so that the effort might matter to someone even if the work does not. As career midway games go, comics is more pick up a floating duck than a ring toss. One halfway memorable thing really does put you in the club forever. Comics has a staggeringly low threshold for initial participation and a lower one for renewing one's dues. Comics will demand next to nothing from some people even as it demands almost everything from others.

In seventeen years I've never had a workday that matched what my conception of a day at work should be. I'm happy to put off what should be routine as if I'm holding at arm's length grand projects I must steel myself to achieve. I write sentences that can't be diagrammed and let them be. I finesse entire paragraphs that allow me to avoid making a single phone call. I've lost too many interviews to count, and others I just stare at the tapes or MP3, because something in me is too paralyzed to continue transcribing. I've made up things to get past screwing something up, fantasies right out of whole cloth, and nobody's noticed. I have a job that takes me a few hours a week and I've yet to fill the remaining hours with anything worthwhile.

Comics is the place where I'm the least scared.

*****

I don't remember the coma. I have a single flash memory of a nurse in a blue shirt trying to turn me over, a nurse I never saw again. Otherwise: darkness. I woke up with a tube in my mouth. I woke up. I'm plugged in. There's something in my neck that drips into my heart, to help keep me free from pain. A band occasionally tightens around my arm to check my blood pressure and I'm surprised every time it happens. I'm dancing in place. They have my legs in a device that moves them as if I'm one of those foam creatures under a window of plastic with dials attached to my joints. I find out later that it's a machine to keep the blood in my legs from clotting.

If I learned anything that first 48 hours awake, it was to focus on the next event: the next breath, the next five minutes, the next question written on the notepad, the next time someone might come into the room. To my surprise, after a life of avoidance I'm not that bad at taking things as they come. Although come to think of it, no one carves time like an unproductive writer.

The specks on the ceiling panel above my bed occasionally crackle and surge into cartoon drawings outlined in blue. I blink -- two, three times -- and they disappear.

*****

My brother told me that this entire ordeal was my body's last-ditch attempt to keep me from seeing

Green Lantern. My brother is a very funny man.

I spent way too much time over the next several days thinking about things like the Green Lantern movie. By "too much time" I mean in the overall scheme of things, certainly not in terms of what I was doing. I was living 22-hour days, from 2 AM to 12 midnight. I could barely sleep, and as every experience in the hospital was a new one the days seemed even longer than they were. I had nothing but time, punctuated by short bursts of telephone conversations where I made little to no sense, where all I wanted to do was to thank the person calling over and over again. I tried to think about anything except comics, but I don't have enough in my life to fill that many hours. So I thought. And thought. And thought. Big, unclear, messy thoughts.

The thing that's remarkable to me about

Green Lantern was the severe dichotomy of rhetoric over the fact that the movie performed greatly under expectations. On one side were those gleeful about it, as if enough money to cure a disease going down a hole were some thrilling victory for right-thinking individuals everywhere. On the other side you have those out to willfully deny the failure, to suggest that $100 million was nothing to sneeze at, it opened well with this group of people and that indicates this, hell yeah we're doing a sequel and before you say another word where is

your multi-million dollar movie that opened in thousands of theaters, Mr. Critical? Our chatboard arguments now come pre-made.

I don't know much about the film industry, but I figure that a movie that doesn't perform well is a movie that doesn't perform well. Sometimes art doesn't hit. As much as the message board pundits and twitter prophets might proclaim with strong words cribbed from the Internet Handbook Of Effective Declarations the reason why one thing becomes successful and another doesn't, they don't really know, either. Life goes on. Something opens seven days later. Other movies get made. Shouty Batman

is back next summer, and the comics people that care to bask in reflected glory can strut around for the three major cons after it opens to 1000 trillion dollars or whatever. It's a curious thing to embrace as meaningful. It's barely a thing at all. Every movie's credits make me sad.

It might have been the medicine doing its job, but I couldn't help but conflate

Green Lantern struggling to scramble past Hop on the year-to-date lists with the wider DC Comics moves of the last couple of years. I'm not sure I should. But there it is. It's largely, I think, because I don't understand the publishing moves, either. It feels like the last few years for DC have been one long period of family-rattling misbehavior by a formerly stand-up husband. I understood that DC, with their simmering resentment at being the industry's stand-up, good-guy, supportive partner to a Direct Market with a "I Love Marvel" tattoo on its bicep and the House That Jack Built on the speed dial. I understood a lot of things about that old DC.

I remain largely clueless about the new status quo. I still don't understand exactly what it is

Diane Nelson does. I don't understand what was so right with DC Comics the last several years that they chose to double-down by creating a three-headed brain trust out of people in the thick of that company's recent orthodoxy, nor do I understand what makes those people natural agents of change if that what's called for. I don't understand how DC looked at its current talent pool and roster of characters and decided that 52 new titles was the best idea, and I have serious doubts they can maintain it in a successful way over six, twelve, eighteen months without a tremendous burn-off of resources that could have been employed to much greater effect in less dramatic ways. I know that because it's DC they'll cite numbers we can't see and declare it a success no matter what happens. That part I get. But I don't understand how as a media company DC can put all their eggs into a Green Lantern basket and not have things like TV shows lined up for

Kid Eternity and toy-generating property supreme

Dial H For Hero -- or some equivalent, something, anything that indicates they realize the richness of that character library. Frankly, I may never understand this era of DC. I just hope there's another one.

I had a very childish reaction to DC's big news of a line-wide re-launch and same-day digital offerings. I realized as I was lying there in the hospital watching cable TV's endless cycle of late-period

Tim Burton movies that I had this reaction because the announcement frightened me. It felt to me like the death of industry, or at least my admittedly child's idealized conception of industry where people make things and then are paid fairly for the fruits of that thing. Comics has given up industry for proximity. That's not exactly breaking news. Too few people make comics for the reward of making comics, both because there are fewer and fewer rewards and partly because there's a promise for a greater return down the line. It seems entirely appropriate that as comics became more invisible to average folk, disappearing into comics stores, the physical product would in time begin to matter less and less to the folks that own and make them. I think what bothered me most is that the

Green Lantern movie briefly turned the talented writer

Geoff Johns into a young guy standing near a major motion picture, a guy that wears a black t-shirt in photos to stand in dramatic fashion alongside his attractive employer. In a better world, an opportunity like this would have felt like an impossible bonus to a richly successful life, and the writing career itself would be the story, not suggested as a prologue to something that really matters.

*****

Being in comics long enough allows you special insight into large, dysfunctional groups of people, which is handy when you're living in a hospital. The sooner you learn to accommodatingly plug into the staff's work day as opposed to continuing to demand that they find a way to work within the confines of the artificial constructions you dragged in there with you, the better things go. Ask for your sleeping pill two hours after everyone else wants one. Negotiate for special attention during the next downtime in exchange for quickly excusing them right now when they're obviously busy. Don't ask for anything at the time the person likes to do their paperwork. Being in a bed for 24 hours a day is not unlike being behind a convention table, except the bathroom is closer. Hospital gowns and nurse's uniforms are the original cosplay.

*****

It's the longest period of my life since age four that I went without reading a comic book. The wonderful thing about that is they became strange again, full of conventions and assumptions that are just a step or two beyond instant comprehension. All art is like that, theater to sitcoms to pop music, and if you step away for long enough the mystery of them appeals even when the content falls short. Because comics count more on the reader than most forms, it's that much harder to make a critical point -- you really are reading a different comic than anyone else has. There are people hooked on narratives, and people that only look at the art, and people that hang onto moments, and people that prefer it when the invisible mechanisms of the form hold greater and more obvious sway. There are people that pick up signals and signs related to a certain experience either received or adopted and judge art if it hits all of those buttons or not. They're all quick to tell you that the other people are doing it wrong.

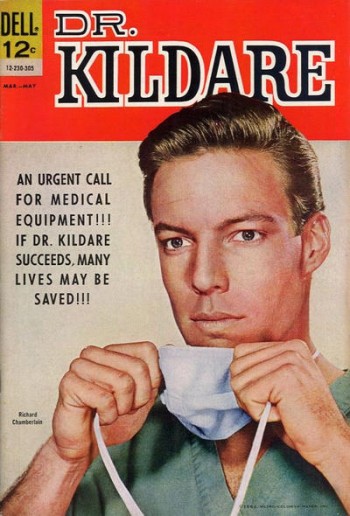

Even worse, to love comics too often becomes a loyalty test of singular devotion according to specific, ascribed parameters (all of comics, art comics, superhero comics, strip comics, manga). And yet there are people for whom comics is an occasional thing, an avenue for nostalgia when the various Marvel soap operas meant the world to them, or a pleasant side trip from prose into

Persepolis during last year's book club. You used to be a comics fan if you owned half a shelf of

Peter Arno books, a few

Peanuts volumes and something by

Bill Mauldin. Now an entire room devoted to comics and toys and original art might get you noticed, but maybe not even then. The demographic that comics has the hardest time welcoming in isn't one defined by race or gender or age but by passion. People don't need to love comics as much as you do to have a perfectly rich and meaningful relationship with the form. There's no one right way to read a comic. There's no one right way to read comics.

*****

Walking for the first time after it's been a while is interesting because you have to push past a frozen state of the kind you might suddenly develop if you were trying to be very quiet, or stopping in front of a door having forgotten something behind you. It's like breaking out of the longest kind of pause.

*****

Sometimes I think I hang around comics because in some deeply troubling way I'm not finished with them yet. It helps that comics-obsessed people my age benefit from another accident of cultural history, the good fortune of being dragged into new and exciting expressions of comics art at just the age we were ready to read them, a period 1980-1994 that shoved a lot of folks into their early 20s without any intention of missing the next big thing or just reveling in more of the same. That showering of riches, all the really good comics and the great ones and even the increasingly cleverly satisfying pulp wringing monthly miracles from tired characters, it's like comics made a promise to a certain group of us and then, for the most part, kept them.

Every person passionately interested in an art form thinks that passion fascinating. In other art forms, however, there's an ease and commercial context to that initial relationship that makes coming to terms with it an answer to a throwaway question on a panel, or the first response in a 10-part interview, the part most likely to be cut and something almost always laughed over. Comics is odd, a medium of heartbreak and musty smells and approximations, and it doesn't have an easy commercial element except for a lucky elite. A very small number of people take to them in that wholehearted way that seems more common to other media. Art comics has a tradition where not long ago its champions fell in love with the form when they had so little access to its history and lived in such artistically fallow times they had no choice but to believe in comics that hadn't been made yet. Like the physical items in many collections, we carry all of it with us, the comics we loved as a kid and all the barely-formed reasons why, the comics that opened our eyes, the comics that we attach to a time and place, the comics that devastated us as adult readers for their skill and insight, the comics that we helped other people enjoy. The model that dominates comics discourse is self-inventory.

I know less about comics than the day I took my first job in its North American industry. Some days I wonder if they aren't better understood on multiple continuities of genres like fantasy and memoir rather than as a thing unto themselves, others I'm sure I'm just about to find the secret, obvious link that connects

Joe Maneely,

Cliff Sterrett and

Edmond Baudoin and present it in a way a child could understand. I'm curious about what's been lost when comics became for some of us something to consume in the presence of other comics fans rather than the viciously lonely but sustaining act reading them used to be. I question how I perceive reality differently for watching 100,000 fistfights without repercussion, millions of deaths executed somewhere off-panel. That's the ultimate failing of mainstream comics, right? They trade in realistic actions but the consequences and context slip further and further into fantasy, so that we stand stunned when a real world incident that wouldn't merit a panel of costumed adventure ruins lives and causes grief on an unimaginable scale. I question how many comics will finally be enough, and what's taking me so long to get there.

I'm not even sure I know how to read comics yet.

When I was younger, I would tell people that one reason I liked comics is that the beginning was just out of reach, that you could on a summer weekend shake the hands of men and women that at least for comic books were there at the start. You could comprehend the whole affair, particularly if you valued them first as art. The older I get the more I prefer the churn, the more I feel a kinship with the dead-ends and false starts and careers and companies that never quite took off, the ten-cent rooms and wicker baskets on porches at lake cottages over the hardcover editions and deftly arranged library holdings. At this point in my life I'd prefer to read the complete works of a defunct independent comics company from the 1980s than the fruits of the latest top 100 list. I'm sentimental now, and that's a part of it, but I also think there's something to a form that's constantly slipping out of your grasp, that's broader and deeper and weirder and more intense than even the excellent works that sifts to the top. Unlike prose or film or theater, we read comics as a window to other comics, comics we may never see, comics that may or may not be out there. We read all the comics we've ever read and all the comics we've yet to read.

****

I'm getting better. I'm still sick. Every day a nice lady comes over to the house and stuffs gauze into a hole in my body. I take pills. I'm on a strict diet that I can't ever quit. I feel beat up and exhausted, the Sunday morning of a four-day convention bender with two hours of sleep the last three evenings and a ripping headache but nothing in the way of happy memories to justify the diminished state. I can make it around the block on foot with some effort, but I need to lie down for a while afterwards. I can only sit up to write a few hours a day, and my concentration, my ability to make what I'm writing reflective of how I'm thinking, for better or for worse, that's been slippery. I feel less than wholly human.

I am extraordinarily lucky. Hundreds of millions of people go through worse every single day. Initial diagnosis aside, I won the health lottery something like five times in a row there. I am so, so, very lucky.

I realize that it's self-absorbed in the extreme to write something like this. As a writer, I need to write these things down so that I can possibly figure them out, both in the doing of it and then later on when I feel the need to look back.

My hope is that by publishing it some of you will start getting check-ups again if, like me, you'd stopped. I hope that you'll be skeptical of every initial diagnosis. I hope you embrace the inevitable fragilities of getting older with good humor and perspective and forgiveness. I hope that you're the friend and family member to someone else in this situation that my friends and family were to me. I hope that you take nothing for granted. If you don't have enough insurance to make this kind of thing easier on you and your family, and believe me when I say that minimum of comfort makes a world of difference, then I hope you'll at least familiarize yourself with the programs and processes that can help you. I hope that you'll step back and for a moment appreciate your seat on whatever side of the window you're on concerning your interaction with comics, this most remarkable and unlikely art form, and the range of human experiences on which it offers insight. I hope that you'll never substitute those things for experiences of your own.

The lesson this summer offered me was granted in the two hours in the ambulance on my way to surgery, when I was forced to look at my life as a potential whole unit, as something with a beginning and a middle and an end. It may have been denial, it may have been an emotional shutdown, but I had surprisingly few regrets, far fewer than used to come to me on an average sleepless night when I was totally healthy and completely terrified. I thought of my friends and family, each one in turn, and the extraordinary yet ordinary thing of loving people and being loved in return. When I die, I may or may not be remembered by a larger group of people for a moment or two. A smaller group of people will keep me with them for a longer while. Eventually those people will die as well, and I'll truly be gone. It's more than enough. People come to comics because they want to matter, but in every way that's important they already do.

I'm in a long aftercare program. I favor sprints over marathons, and now I'm plopped onto a road course that will last until the end of my life. It takes some getting used to. My prognosis is excellent, yet reversals are possible and setbacks are inevitable. A repeat performance isn't out of the question. As much as I continue to get better, as much as smiles greet me at the doctor's office as opposed to calm looks of concern, as much as I feel stronger and more capable and filled with more energy every time I get out of bed, I can't say with 100 percent certainty, "I'll be around this time next year."

Then again, neither can you.

*****

*****

*****

posted 5:30 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives